In late June, two of the Numina team, our Product Designer Meghan Canale and Solutions Engineer Jennifer Ding, joined the IDEO CoLab and Gehl in Cambridge for a design sprint focusing on the subject of Collaborative Cities. One of the features of the growing “smart cities” movements is the ability to use real-time data to aid decision making. This increase in quality and quantity of data both helps cities better understand the public realm and, at the same time, creates trade-offs in human autonomy and surveillance. We spent the week discussing the balance of these trade-offs, brainstorming with our team on methods to build two-way dialogue between citizens and city officials, and empower participation to improve people-first decision making. We focused on answering the key question: How might we engage the public in decision-making about data collection in the public realm, around what data is captured and for what reason? How might we build consensus across governments, businesses, and residents about what data is collected and why?

Through intercept interviews with a dozen citizens with different backgrounds and interests, we found a range of perspectives on public data collection. Some had never previously thought about cities collecting data; however, they were not surprised that cities are collecting data. Those that had thought that cities were collecting data had widely varying opinions from “Security is always used as an excuse to make spaces less private” to “All data collection is fair game if there’s a purpose behind it. That purpose doesn’t need to be communicated every time if we trust our representatives.” Common themes emerged, including that citizens care why and what data is being collected, while also not having a strong personal desire to interact with the datasets. We also interviewed experts across “smart cities” touch points, from a business owner using sensor technologies, to academics and public engagement labs. We learned the value of working with the community to identify the core values and definition of what, for them, constitutes a “smart city.” With these insights we continued to iterate on our ideas to address our design problem.

How might we engage the public in decision-making about data collection in the public realm, around what data is captured and for what reason? How might we build consensus across governments, businesses, and residents about what data is collected and why?

We prototyped several ideas to engage the public, focusing on transparent communication and providing an avenue for public feedback. For one, we explored having an interactive augmented reality (AR) display of information about sensors and the data they collected. This tool would enable citizens to access information on their own time when passing through a space with sensors in it.

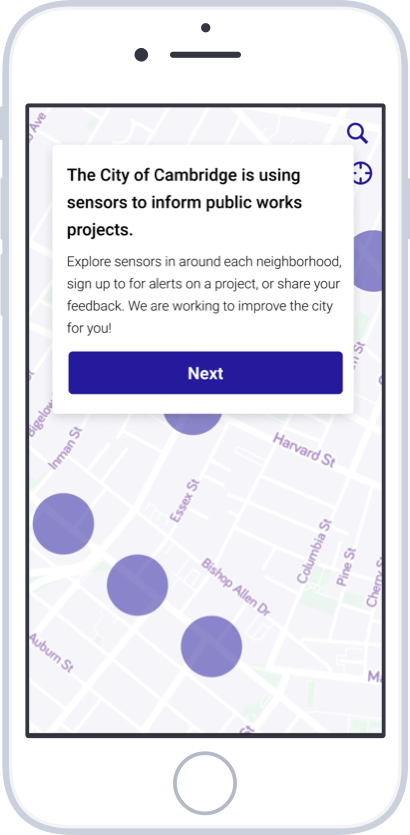

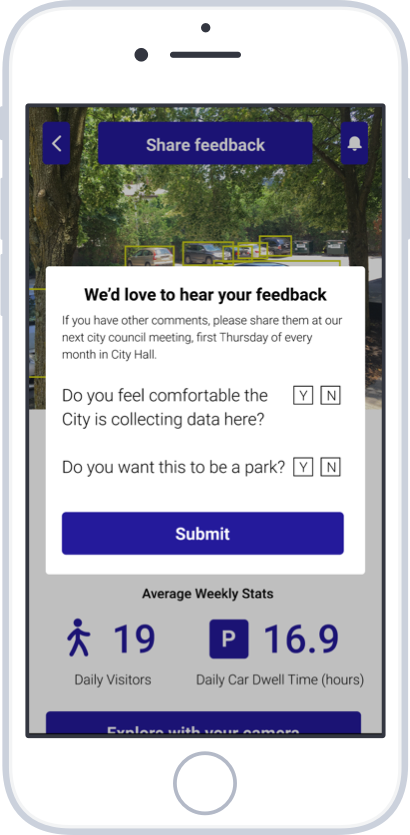

App screenshots show proof of concept app created to collect feedback and facilitate dialog.

The information and these projects do not reflect known active projects nor sensors.

We also prototyped an app that a city could use to show where sensors are, share information on the project they are being used for, what data the sensors are collecting, and opportunities for citizens to provide feedback. We included descriptions of what a city would and would not collect, imagining this information would be available across project phases from proposal, learning/data collection, intervention, and evaluation. Citizens can also “Explore with your camera” when they are at a location with a sensor. The app uses AR to show where sensors are and what information they are collecting.

The experience facilitated conversation, not just because people were interacting with the prototypes, but because they were genuinely curious, wanting to learn more or delve into the realities of public realm data collection. Some also expressed surprise that a city would have such transparent, accessible communication platforms.

Through platforms like this, cities could help lead the conversation on public realm technology deployments, showing a commitment to data privacy and transparency through explicit communication of what is and is not collected. (For example, at Numina, because our philosophy is “Intelligence without Surveillance,” we don’t collect personally identifiable information; we do collect anonymous data points of how objects move through scenes.) These conversations could also help shift data policies into more of a community concern than a personal concern.

These are a few of the many avenues that government, business, and residents can use to facilitate creating a more open dialogue on the value and tradeoffs of real-time data collection. We hope to aid these conversations, emphasizing transparent communication, value of de-identifying and anonymizing data, and engaging citizens throughout the process.